All the programmes are now known. They are all designed to show voters that the candidates are listening to them, involving them in drawing up their programme, and will govern differently. Is this an act that will soon fall victim to the Désir d’Avenir syndrome, or the heralding of a genuine democratic revolution?

The French want to be governed differently. Some aspire to greater involvement in the decision-making process. All are demanding radical change. The proposals put forward by the candidates in the presidential election must therefore be judged against two imperatives: genuine citizen involvement and more effective public action. One imperative sums up the sum of these two objectives: political innovation.

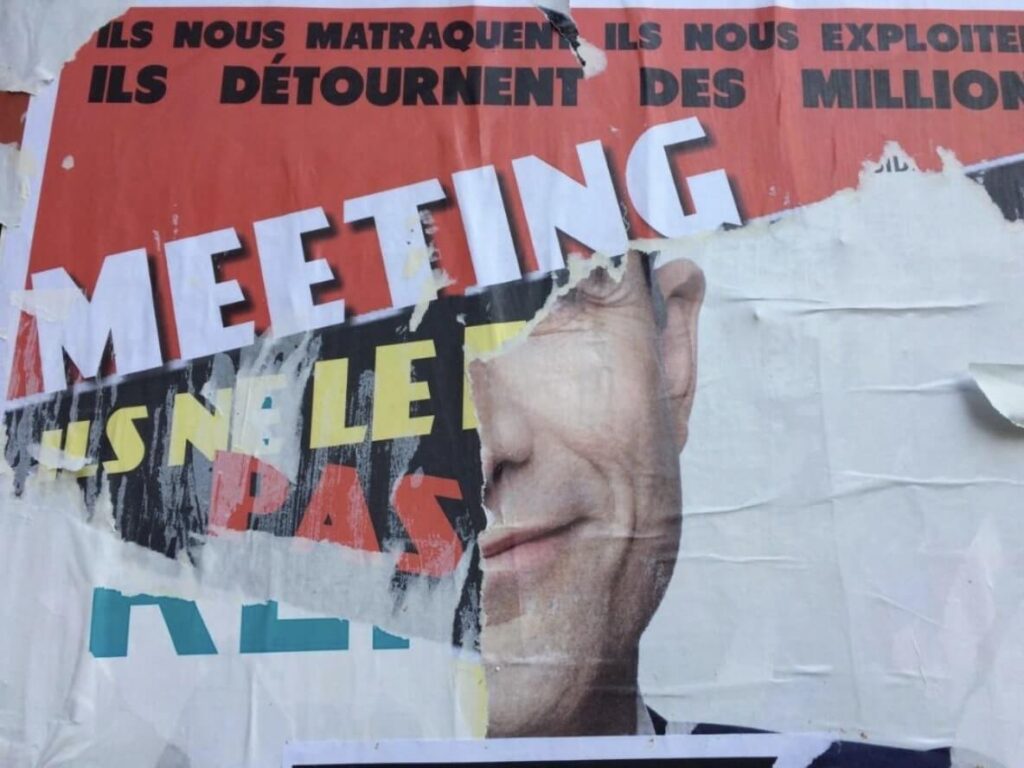

“My programme will be your programme”… Really?

An examination of the meaning of creativity and innovation in politics highlights an unthought-of aspect of the way we conceive of public action. Creativity is the ability to develop solutions in a timely manner, appreciated for their originality, effectiveness and efficiency over time, and thus winning support. It leads to innovation, i.e. the implementation of solutions that emerge from a creative process. In short, politics should be all about cultivating collective creativity and innovation!

A lexical exercise in fashion? No, if we go beyond preconceived ideas, these two notions invite us to radically reinvent our ways of governing, as the French expect. All studies of creative processes underline the fact that creativity thrives on the inclusion of different types of expertise and collaboration between players, transcending fragmentations and overcoming dissensions between approaches, in order to “co-create”. This is exactly what citizens are looking for – a more modern way of governing that is more inclusive and collaborative, less fragmented and sectarian. And ultimately more effective.

Co-creation and the effectiveness of public policies: what are the candidates proposing?

The programmes of the main presidential candidates provide snippets of responses to this public expectation, without forming a coherent whole.

Co-creation of the programme first: François Fillon highlights the consultation of “civil society” and “more than 500 experts”. Even the Front National insists on using “collectives” of “several hundred” experts. So openness is good to see. Others go much further. Emmanuel Macron promised “My programme will be yours” before launching 100,000 “conversations” to draw up his diagnosis, while Jean-Luc Mélenchon consulted an equivalent number of people on the internet. And yet, whatever the method, they all have one thing in common: the final selection is made by a small committee, in a limited amount of time. Normal, you may say, for a process that involves the responsibility of an individual. Of course, but what distinguishes these processes from François Mitterrand’s style of media writing, which aimed above all to choose the language that best resonated with the target electorate, rather than to engage in genuinely open collective reflection?

As far as the programmes are concerned, Emmanuel Macron, Benoît Hamon, Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Charlotte Marchandise of laprimaire.org have a wide range of proposals. They include measures as interesting as the desire, in the case of the former, to give more resources to the evaluation of existing texts and more time to the preparation of legislation, with a citizens’ policy debate, to continue the decentralisation movement, or to allow consensus conferences on certain issues. In the case of the second, to offer citizens the opportunity to submit amendments to a bill via the “citizen amendment”, or to intervene in the legislative process via a “citizen article 49.3”. Mr Mélenchon, for his part, is proposing to set things straight with a Constituent Assembly.

The desire for renewal has therefore been perceived. But the reforms announced are not systematically guided by this dual imperative of co-creation and efficiency. Imagine that an organisation decides to turn resolutely towards innovation to ensure its survival. Would it simply set up an occasional ideas box, allow motions to be tabled at its General Meeting, or change its articles of association?

Really encouraging political innovation means first of all putting creativity at the heart of public action, for example by appointing a Minister of State for Future Generations who works alongside the Prime Minister to ensure that ministers remedy the fragmentation of their action and their insufficient consideration of the future. Encouraging innovation also means embracing the complexity of the issues at stake and resisting the prevailing simplism. In practical terms, this means, for example, that the increased evaluation of public policies should not rely solely on economic tools, but should involve a variety of social sciences as well as the publics concerned. We also need to teach innovation methods to public players and ensure that the State plays a role as a catalyst for creativity. Decentralising more will not be effective unless it is accompanied by a redefinition of the role of central government, so that it facilitates experimentation – absent from programmes but essential to any creative process – learns from it and supports the reproduction on a larger scale of the boldest and most useful measures.

It’s time to put imagination in power through measures like these, and many others. Democracy in the 21st century will be creative, or it won’t be.